A tour of CUDA#

In this chapter we will dive into CUDA, the standard GPU development model for Nvidia devices. To understand the basics of CUDA we first need to understand how GPU devices are organised.

CUDA Device Model#

At the most basic level, GPU accelerators are massively parallel compute devices that can run a huge number of threads concurrently. Compute devices have global memory, shared memory and local memory for threads. Moreover, threads are grouped into thread blocks that allow shared memory access. We will discuss all these points in more detail below.

Threads, Cuda Cores, Warps and Streaming Multiprocessors#

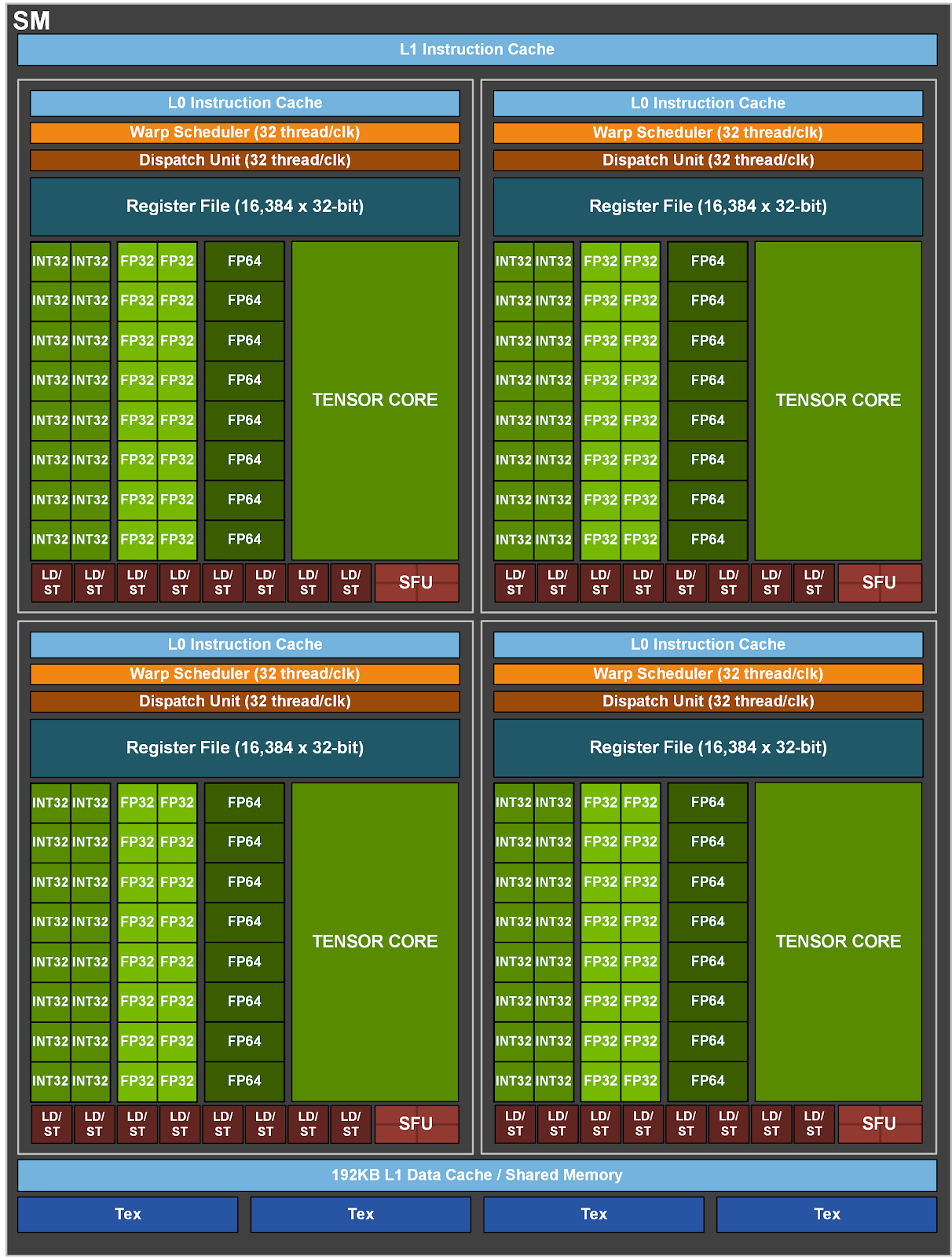

A GPU device is organised into a number of Streaming Multiprocessors (SM). Each SM is responsible for scheduling and executing a number of thread blocks. Below we show the design of a SM for the Nvidia A100 Architecture (see https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/nvidia-ampere-architecture-in-depth/).

Each SM in the A100 architecture consists of integer cores, floating point cores and tensor cores. Tensor cores are relatively new and optimised for mixed precision multiply/add operations for deep learning. The SM is responsible for scheduling threads onto the different compute cores. For the developer the lowest logical entity is a thread. Threads are organised by thread blocks in CUDA. A thread block is a group of thread that is allowed to access fast shared memory together. In terms of implementation thread blocks are divided into Warps, where as each Warp contains 32 threads. Within a Warp all threads must follow the same execution path, which has implications for branch statements that we will discuss later. A Warp is roughly comparable to a SIMD vector register in CPU architectures.

The scheduling into Warps is important for the organisation of thread blocks. Ideally, these are multiples of 32. If a thread block is not a multiple of 32 Cores may be underutilised. Consider a thread block of 48 threads. This will take up two Warps as we have 32 + 16 threads. Hence, the second Warp will not be fully utilised.

Numbering of threads#

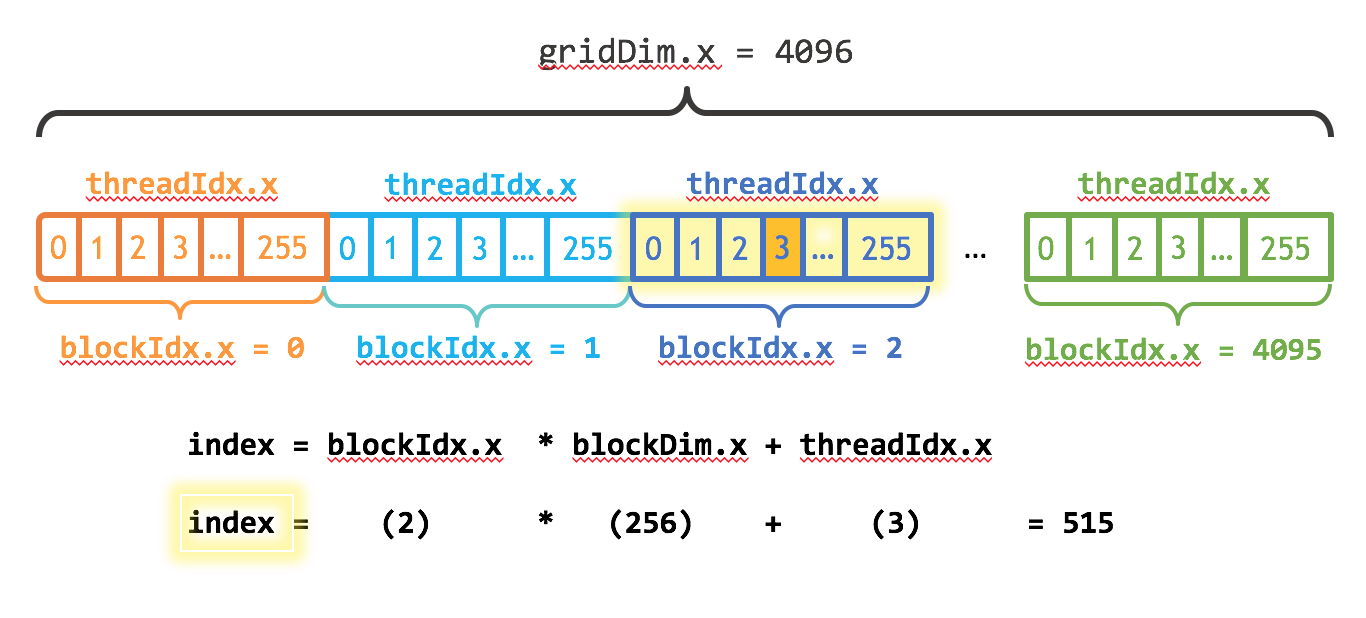

The numbering of a thread is shown in the following Figure (see https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/even-easier-introduction-cuda/).

As mentioned above, threads are organised in thread blocks. All thread blocks together form a thread grid. The thread grid does not need to be one-dimensional. It can also be two or three dimensional. This is convenient if the computational domain is better represented in two or three dimensions. The figure demonstrates how for one dimension the global thread number of a thread block is computed.

Memory Hierarchy#

CUDA knows three types of memory

The global memory is a block of memory accessible by all threads in a device. This is the largest chunk of memory and the place where we create GPU buffers to store our input to computations and output results. While a GPU typically has a few gigabytes of global memory, access to it is relatively slow from the individual threads.

All threads within a given block have access to local shared memory. This shared memory is fast and available within the lifetime of the thread block. Together with local synchronisation it can be efficiently used to process workload within a given thread block without having to write back and forth to the global memory.

Each thread has its own private memory. This is very fast and used to store local intermediate results that are only needed in the current thread.

An example#

The following example from the official Numba documentation uses all of the above mentioned principles. It is an implementation of a matrix-matrix product that makes use of shared memory for block-wise multiplication.

from numba import cuda, float32

# Controls threads per block and shared memory usage.

# The computation will be done on blocks of TPBxTPB elements.

TPB = 16

@cuda.jit

def fast_matmul(A, B, C):

# Define an array in the shared memory

# The size and type of the arrays must be known at compile time

sA = cuda.shared.array(shape=(TPB, TPB), dtype=float32)

sB = cuda.shared.array(shape=(TPB, TPB), dtype=float32)

x, y = cuda.grid(2)

tx = cuda.threadIdx.x

ty = cuda.threadIdx.y

bpg = cuda.gridDim.x # blocks per grid

if x >= C.shape[0] and y >= C.shape[1]:

# Quit if (x, y) is outside of valid C boundary

return

# Each thread computes one element in the result matrix.

# The dot product is chunked into dot products of TPB-long vectors.

tmp = 0.

for i in range(bpg):

# Preload data into shared memory

sA[tx, ty] = A[x, ty + i * TPB]

sB[tx, ty] = B[tx + i * TPB, y]

# Wait until all threads finish preloading

cuda.syncthreads()

# Computes partial product on the shared memory

for j in range(TPB):

tmp += sA[tx, j] * sB[j, ty]

# Wait until all threads finish computing

cuda.syncthreads()

C[x, y] = tmp